When I started researching my thesis on "French culinary criticism" back in 2009, I didn't know if I'd ever find work in food, let alone have the chance to attend culinary school. But in 2012, after a few years freelance writing for various food publications, I found an amazing full-time opportunity as the Social Media & Content Manager at New York's Institute of Culinary Education. Most recently, the opportunity to enroll in ICE's award-winning Culinary Arts program has proved the "cherry on top" of this incredible professional experience — and I'll be blogging about it every step of the way.

The first thing you learn in culinary school is that being a chef is far more complex than most people realize. From your white commis cap down to your stiff-toed shoes, everything is designed for safety, efficiency and cleanliness. In fact, sanitation is the first subject you’ll tackle, learning how factors from temperature to humidity, pH to protein content affect the safety of everything we cook. That may sound boring, but once you’ve studied the many ways improperly handled food can lead to illness, it’s pretty fascinating how rarely we all get sick!

Testing out my chef’s coat and setting up my knives for class

Beyond worrying about proper heating, refrigeration and cleanliness of the products you’ll serve your guests, you also need to learn how not to harm yourself in the kitchen. As culinary students, our tools are our trade, and we’re dealing on a daily basis with fire and knives.

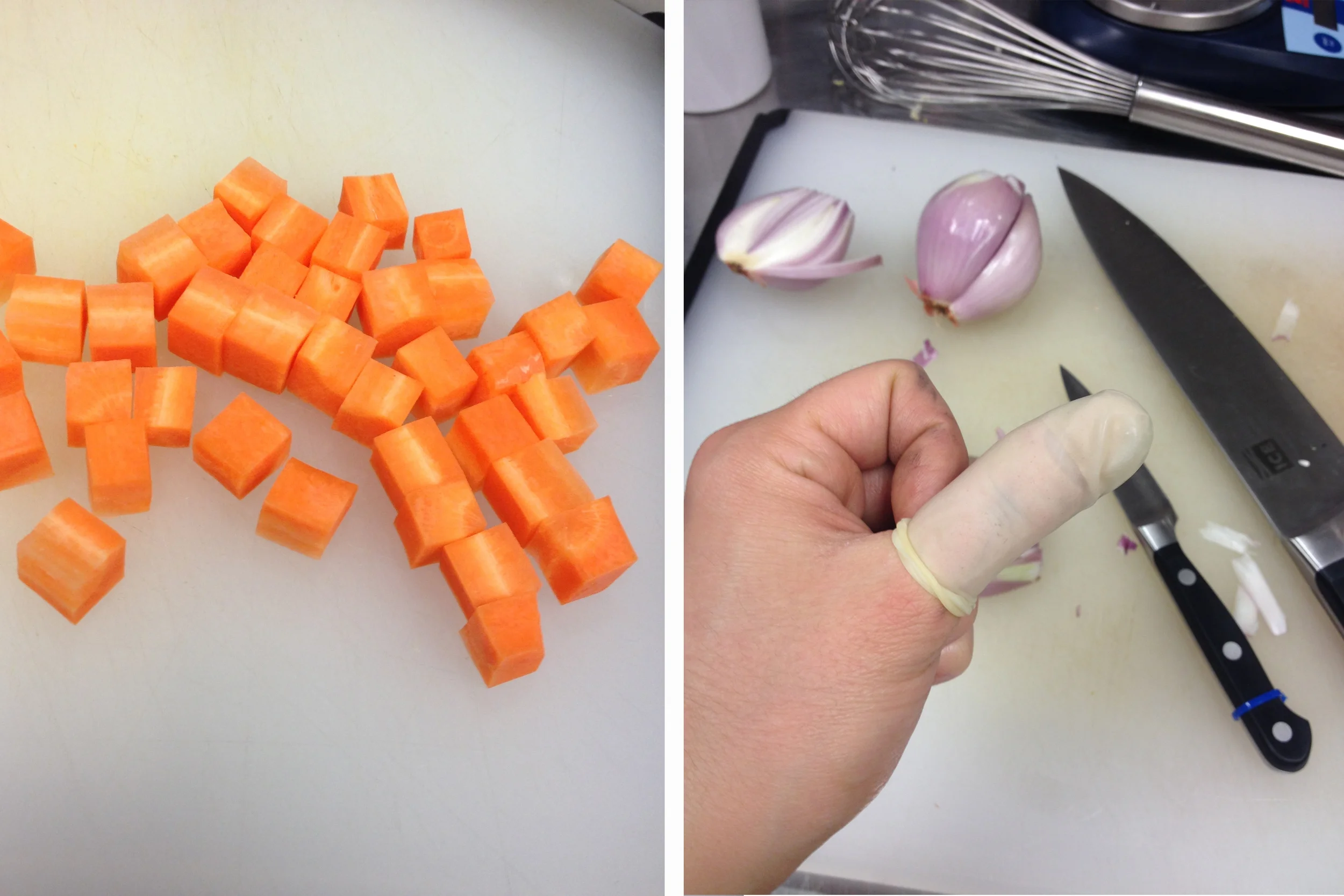

In fact, it’s only when you receive your knife roll that being a “future chef” starts to sink in. Laser-sharp, these knives are our best friends and worst enemies. Ironically, the sharper the blade, the safer you are cutting up your mise en place or filleting a fish. But even the smallest knives have a big bite—I got my first culinary school cut by nicking my thumb with the tip of a paring knife.

Medium dice carrots and my first culinary school cut

As our first hands-on knife skills challenge, Chef Michael Garrett taught us to wield our massive 10-inch Wusthof chef’s knives to break down oddly shaped carrots and potatoes into small, perfectly square, half-inch cubes—a process chefs call “medium dice”. It’s a frustrating skill to get the hang of, but as you go through the patient repetition of crafting each little square, there’s a deep sense of satisfaction to the process.

In addition to honing our knife skills, our first days include learning about raw ingredients. First up, herb identification. Have you ever tasted fresh marjoram or chervil? Even as an accomplished home cook, I hadn’t. But the most shocking herb to taste raw might just be oregano—it’s essentially a fuzzy fireball! From there we moved on to cheeses (which might be the most indulgent day in all of culinary school). From fresh ricotta and tangy buffalo mozzarella to creamy French explorateur and funkier chunks of pont-l’évêque or taleggio, we tasted flavors from all over the globe and still had only skimmed the surface of cheese world.

Herb Identification

We also dove into oils and vinegars, tasting them on their own and experimenting with various vinaigrettes. We also learned to “emulsify” these concoctions, adding and whipping the oil gradually to create a thicker texture, somewhat similar to that of the salad dressing you buy in stores. Best of all, we learned to make the mother of all emulsions, mayonnaise, from scratch.

Chef Michael Garrett schools our class in the art of mayonnaise.

From the choice of our ingredients to the precision required for each preparation, our day-to-day work as culinary students is all about learning to be focused and to multi-task. We carefully craft dishes—sometimes in mere moments, sometimes over the span of many hours—that our guests will enjoy for just a few minutes. Everything is a balance of time and precision—do it fast, but do it right— and the line between success and failure is about as thin as it gets.

You would think it would take a very specific kind of person to do this job, but our class couldn’t be more diverse. From former marketing executives to recent high school graduates, medical professionals to fashion photographers—we all have the same passion. True, some of us will end up in restaurants, while others will work in food media, launch their own small businesses, or any number of possible futures. But we’re all here because we love working with our hands and learning to craft the only kind of “art” that humans can fully interact with: food.

Read more about my adventures at ICE at blog.ice.edu.